November 2021

The digital age?

In rural areas of Inner Terai - the field of CEPP, the Centre for Educational Policies and Practices - the computer was not present until now. Digital literacy, part of the school curriculum, was taught... on the blackboard. At present, a real revolution is taking place: the ongoing construction of major highways brings the modern world closer, with new opportunities ánd needs. Furthermore, due to corona and the associated lockdowns and closures of schools, the government was forced to focus on digitization and distance learning - not an obvious choice, especially in poorer environments. CEPP fieldworkers therefore initially focused on teaching in small groups, in the open air. In rural government schools, digitization is often limited to the introduction of a computer, without the associated necessary training on its use. Making use of the lockdown period, all CEPP staff were first given a comprehensive action-training. They then developed an introductory course in English ánd Nepali.

|

| 90 teachers enthusiastically participate in the practical training. |

Thanks to BIKAS and HeSpace Children's Foundation, the local Municipality then handed over some additional sets of smart TVs to trained teachers, something which is not done by many donors. Computers are often left underutilized as teachers don't know how to use them properly.

|

| Following the training, the Municipality hands over a smart TV to a trained teacher. |

CEPP therefore wishes to organize follow-up learning opportunities, for example about the free digital lessons for the different grades that the government is providing (www.olenepal.org). These activities can now even be used off-line, by downloading them to a pen-drive that can be transported physically - as there is no Internet connection in all the schools of the area yet.

|

| Children are quite interested in this new way of teaching and learning! Please also notice the orderliness and child-centred design of the classroom: floor sitting, use of educational posters and teacher-made materials. |

Integrated teaching

The Nepali government has chosen the path of 'integrated teaching': instead of teaching different subjects separately, teachers will integrate subjects around a theme chosen. This is new for developing countries like Nepal. CEPP is contributing to the effort by promoting the greening of schools and by teaching life skills to students of Class 6, 7 and 8. Promoting self-awareness about the changes in adolescence and handling emotions at that stage is the main focus. The purpose is to prevent early marriages and help teens to continue schooling to higher grades, a stance also supported by the government and by Unicef.

|

| Pupils plant trees for shade |

|

| Adolescents do exercises and watch videos illustrating the choices made by their peers. |

Emotional well-being

During the later days of the lockdown, staff visited the families to check how they were feeling and how the children were doing. Children were busy with household work and playing. They were not as stressed as in urban areas but longed for school to start again...

|

Providing quality education goes a long way beyond a suitable school building: the motivation and well-being of all participants in education are equally important. These are but a few of the initiatives CEPP has taken in recent months in its cooperation with rural government schools in Sindhuli and Makwanpur District, the hilly areas south of Kathmandu and north of the Indian border. We will document further efforts in the next issue of this magazine! Please take a look at our earlier contributions on the BIKAS website too (https://bikas.org/EN/from_school_to_school)

Your donations on the BIKAS account BE32 2200 7878 0002 are much appreciated and well-used. Please mention 'From School to School'.

Thank you very much!

|

July 2021

Improving the quality of education is central to the functioning of CEPP, the Centre for Educational Policies and Practices. It is sometimes difficult for us to fathom the real state of education in Nepal. In this Bikas issue we therefore present some points of view from an article by Binod Ghimire, who reports on human rights, social justice and education in the newspaper 'The Kathmandu Post'. We confront these views with the experience and the expertise of Teeka Bhattarai from CEPP.

‘School dropout remains a challenge, survey report shows’ (Binod Ghimire, The Kathmandu Post, 31 May 2021)

Despite an increase in enrolment, a high dropout rate remains a challenge in education. In 2013-14 the enrolment rate for Grade 1 was 91%. According to the research report, that has now risen to 97.3%. However, the government's economic survey report unveiled on Friday shows that more than two-thirds of students enrolled in Grade 1 leave the school system before reaching Grade 12, the final year of school education. The retention rate to Grade 10 is also poor: out of 100 students, 36 leave before reaching Grade 10. Education experts believe that poverty is the main reason, as parents from poor communities often have to use their children's income to support the family. The low education of the parents is another factor. The lack of a good school infrastructure and a poor learning environment are also responsible for higher school drop-out rates. Although the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology receives the highest budget, more than 85% of it is spent on the salaries of teachers and school staff, while only a small part is allocated to materials and improving the quality of education. “Adequate budget is still lacking, especially in the post-Covid situation,” says Bal Chandra Luitel, professor at Kathmandu University. “Students' learning performance was not the same during the pandemic. Reducing drop-out and improving quality should have been the government's priority. Also, the necessary programs to promote learning activities during the pandemic are lacking. To this end, the federal government will have to work closely with local and provincial authorities.”

‘What about the quality of education?’ (Teeka Bhattarai, CEPP, 4 June 2021)

|

| A classroom like this is no exception in the countryside.There is no school furniture, no didactic decoration. This situation points to material poverty, but also to a lack of motivation on the part of the teachers and a lack of involvement of the local community. |

|

| Improvement is slow. The classroom is neat, there are benches and the teacher has exhibited drawings of the children, a sign of appreciation. |

Teeka Bhattarai, education activist and initiator of CEPP is critical towards the conclusions of the survey report and the opinions of the journalist:

“Mostly the parents are blamed for their ignorance, or poverty, disregarding the fact that they are well aware of the value of quality education and are concerned about the future of their children,” he says. “These opinions are common and have been around for a long time. This is the escapist narrative against which we have been struggling. The reasons mentioned or the narrative used are only marginally true,” he adds. “The government takes education seriously only in rhetoric. The government policies are infrastructure-oriented and the system runs inefficiently. There is a big shadow of private schools. Private schools thrive on the failure of public schools; children of the policy makers and other influential people including most teachers attend private schools… The popularity of private schools does not encourage the teachers from the public schools to do well; neither does it put pressure on them. Public school teachers are paid by the government, but they are not held accountable for their own performance, or for the success or failure of their students. The quality of education offered by many teachers is low, a fact for which they are only partly to blame, because their training is theoretical and disregards the reality of rural communities or ethnic minorities. The poor school infrastructure and lack of educational resources in remote areas add to the problem. There is little stress on lower grades and the local cultures and languages are not valued or taken account of in the school curriculum. Worse even, children who speak other than Nepali are discriminated both by the system and the teachers… Teachers come from a relatively well-to-do background and the parents often come from a poorer background – their concerns or reactions are not counted. Yes, schools are not interesting for children also for all of the above reasons. In truth, the main reason for dropout is that public schools don’t deliver quality for whatever is spent…”

Ani ke garne? (What to do?)

|

| As long as the teacher is motivated, education can happen anywhere. During Covid, parents invite teachers to teach outside their house. |

To improve the quality of education in its working area, the rural districts of Makwanpur and Sindhuli in southern Nepal, CEPP, in cooperation with the government schools and local municipalities – focuses on ECD (Early Childhood Development, nursery school) and the lower grades, which are at the basis of education and lifelong learning; – values the local cultures and languages; – motivates and trains the teachers, paying special attention to child-centred learning environments; – informs the parents about their rights and encourages them to become active members of SMCs (school management committees); – takes part in the national debate about education and wishes to influence educational policies, both at the local and national level.

|

| With a motivated teacher and in a child-centred laerning environment, children are eager to learn. |

Dear readers, thank you for your continued support to our project ‘From School to School’. Because of the current difficult situation, CEPP faces a lot of challenges. Do you wish to support their efforts regarding the quality of education in Nepal? You can do so on the Bikas account BE32 2200 7878 0002, using ‘From School to School’ as a reference.

|

| CEPP organises a practical training for ECD teachers. |

April 2021

Do we close the schools or do we choose to keep them open with the necessary measures? It is a question that concerns not only our policymakers and educators, but also the national government, local authorities and teachers in Nepal. A normal school year runs from late April to the end of March, but Nepal went into full lockdown from 24 March 2020 onwards, and it took a long time before teachers could use alternative teaching methods to more or less cater for the needs of the students. Ever since September 2020, the government has been encouraging virtual learning, and authenticates study from five different modalities: face-to-face in small groups, through radio, through television, online study and offline study. All of these teaching techniques are new though, and without proper guidance, teachers may be at a loss. Moreover, a recent report by Unicef shows that three out of ten students do not have access to any of the virtual learning mediums.

|

| Digital televisions are entering education. |

The problem is most prominent in the schools in the remote countryside because of a variety of reasons. The municipalities have only been made responsible for education in their area since a recent reform in 2018 and still lack experience and the necessary staff, especially to deal with these difficult circumstances. Teachers working in rural schools may have little (and sometimes no) formal pedagogical training, they may live away from their teaching area and, due to the ban on travelling during lockdown, be absent from the schools or the villages in which they normally work. Only very exceptionally do teachers have any computer skills or access to a computer. Hardly any rural government schools in CEPP’s working area have a computer at all. Computer skills form part of the curriculum, but are taught… using a blackboard / whiteboard. Villages and schools may be void of electricity, and Internet access is still rare.

|

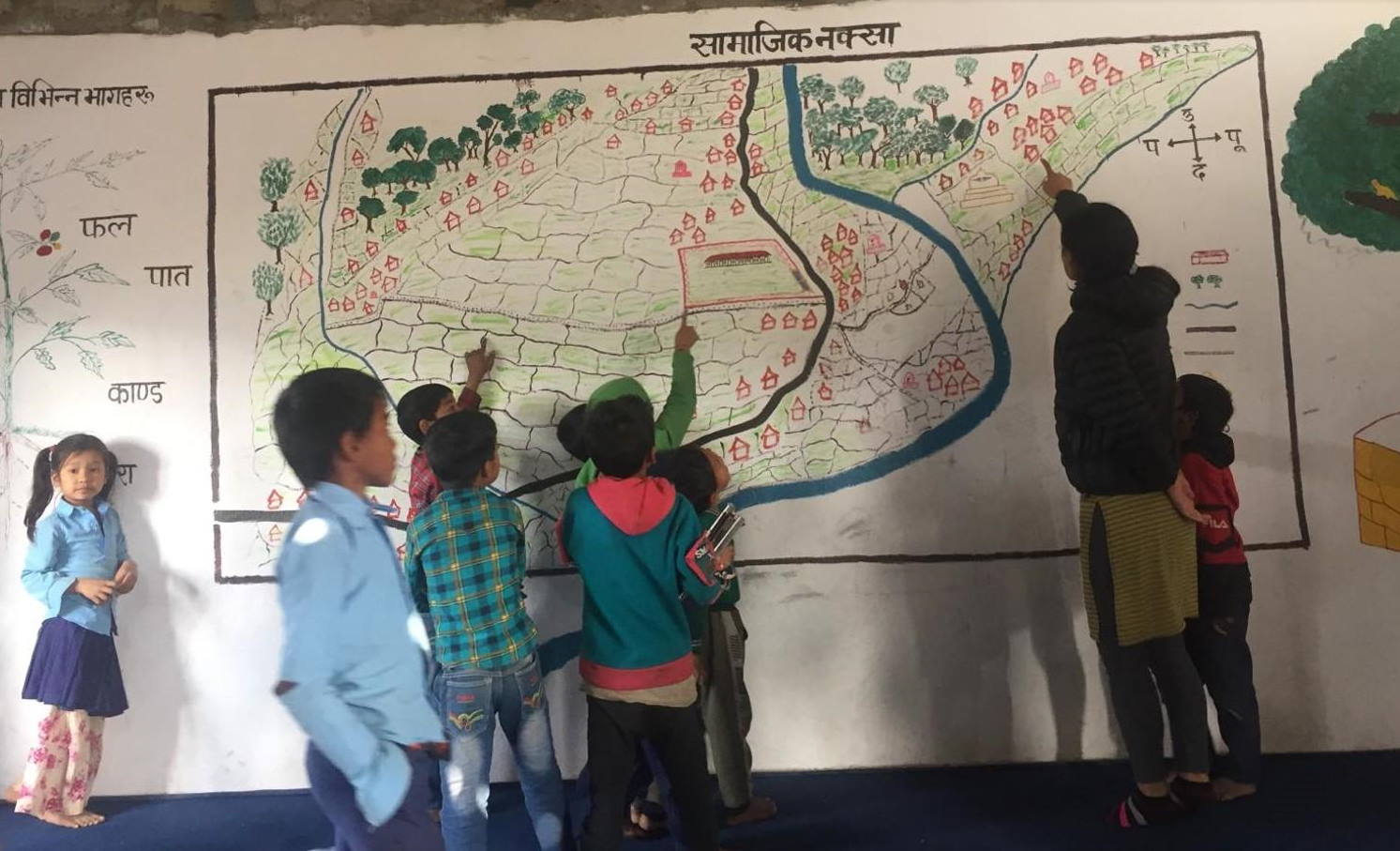

| Children of Grade two look for their home on a social map drawn on the wall. |

How have our CEPP partners (the Centre for Educational Policies and Practices) been trying to cooperate with the schools and municipalities in their working area, the Districts of Sindhuli and Makwanpur? By now, schools have reopened and they are struggling to return to normality. The Nepali government has extended the academic year up to mid-April and has reduced the curriculum by 30 %, giving relief to panicking teachers, trying to ‘finish the course of study’ by all means. A return to normality is a relief for most teachers and schools. Ideas that flourished around learning outside the school, and away from the course books, have been replaced by the routine teaching based on textbooks, often restricted to repetition and memorizing contents. CEPP has continued its usual job of speaking to parents, training the school committees about their responsibilities and improving classrooms with the help of parents and teachers.

Many schools, including Hakpara and Jutepani in Sindhuli District, have added pre-primary grades (called Early Childhood Development Grade or ECD) under new provisions by the Municipality. They have appointed ‘teachers’, but these have not received any teacher training. Hence, in the coming months, CEPP is planning to offer training that puts the children at the centre of the teaching process. As yet, education in this grade does not go beyond teaching the Roman and Devanagari alphabets, with many words to memorize and an exaggerated emphasis on spelling and on languages that may be unfamiliar to the children, namely Nepali and English. CEPP wants to emphasize the importance of the children’s mother tongue, which is often Rai or Tamang in these rural villages (only two of the more than 100 languages spoken in Nepal).

|

| Children are preparing a vegetable garden - they remove the stones before ploughing can begin. |

The hard work of establishing kitchen gardens and the greening of the schools was set back by the closure of the schools. Attempts have been made to revive them but the process does not get adequate attention yet in the race of finishing the textbooks. Given that land is provided and there is a level of enthusiasm in the school and a level of support by Bikas and HeSpace Children’s Foundation alike, priority is now given to establishing a greening resource centre with a tree nursery and a kitchen garden. A specialist is hired to encourage local people to engage themselves. A well with a pump is to be set up for irrigation. Digitization has been started with the purchase of tablets that can be used with a pen-drive, to beam images and content onto a flat surface. A digital literacy training for teachers is being considered, but is yet to be materialized. CEPP staff are busy working on a project to support the Municipality to meet the central government’s requirement of developing a local curriculum, teaching children about things that are important locally. Getting somebody from outside the community would risk an inappropriate curriculum formulation and would make CEPP miss the opportunity to work with the Municipality and have an influential relationship on school matters. In Belgium and in Nepal alike, all parties concerned are struggling to meet the children’s needs in education. Nepalese educators are looking for a balance between contents and teaching methods, between tradition and innovation.

If you want to encourage CEPP’s efforts in this respect, your contribution is welcome on the Bikas account 32 2200 7878 0002. Please mention ‘From School to School’. We truly appreciate your interest and support!

January 2021 - Back to Nature

Two thirds of the Nepali workforce is engaged in agriculture, but productivity is low, and the more people get an education, the more the status of agriculture is threatened. Nevertheless, because of Covid 19, many people could not work in the cities or in tourism anymore. They had no choice but to return to their native villages and be engaged in farming once again. We asked Teeka Bhattarai, who leads our partner organisation, the Centre for Educational Policies and Practices, why he thinks the idea of agro-ecology is so important, especially with regard to education. Do Nepali children have a balanced and healthy diet? How can we encourage local communities, ecspecially the parents, to pass on the skills the children will need to produce a wide range of vegetables and raise farm animals, and be proud of their achievements? How can we instil a love of the outdoors and respect for nature in the kids? We already show a practical example: the construction of a school vegetable garden in Hakpara, Sindhuli District.

This is Teeka’s response:

In Nepal, as elsewhere, education is often regarded as a liberation from producing your food. Agriculture is even presented as an opposite to schooling. A Nepali proverb says that ‘if you don’t study, you end up in earning a living by plowing’. Of course, this idea is not only specific to Nepal and it is also a recent one. In contrast, agriculture has also been boasted as the best occupation followed by trade and service for the independence and self-reliance it provides. However, modern agricultural education is focused on growing food for money rather than for its own purpose, let alone for learning. Here I wish to share how agriculture is a double pedagogy for young children and can be an important part of the existential knowledge education should impart. Teaching agriculture is a double pedagogy because, besides teaching techniques useful in farming, it can instill many habits that are desirable from an early age on. It is even more important to learn agro-ecology (ecological agriculture) as it seeks to combine nature and human intelligence. Farming is a knowledge-intensive enterprise, even though most people tend to think that anybody can do it. In Nepal, people have been engaged in agriculture for centuries. Farmers can do it because they have ‘inherited’ knowledge from their ancestors. I think that, even in Europe, many ‘new’ farmers immediately appreciate everything that is said here. On a table below I have tried to establish some foundational life skills that can be taught through agricultural activities:

| Foundational life skills | What agricultural activities offer |

|---|---|

| • Creativity | • There are always multiple solutions |

| • Exploration | • You keep on trying as there are many variables |

| • Enthusiasm | • Changes in crops overnight keep enthusiasm high |

| • Physical movement | • Body movements have to be precise |

| • Purposeful act | • The results of your actions are explicit: you sow to grow |

| • Patience | • The results of your actions are not immediate |

| • Integration | • It integrates many disciplines: social skills, biology… |

| • Planning | • You must plan carefully to get results |

| • Adaptation | • Sun, air, water, soil are dynamic: you must learn to adapt |

| • Living with contrasts | • The world is not perfect – still you do your best |

| • Observation | • Learning to observe dynamic relations |

| • Concentration | • You cannot do much without concentration |

| • Resumption | • You have no option but to try again when things fail |

| • Thinking out of the box | • You have to be dynamic to get results |

| • Bounce back! | • Plants too struggle to overcome difficult circumstances |

| • Critical thinking | • It is an interplay between existing and new knowledge |

| • Karuna (kindness) | • You love what you grow – plants, animals, even humans |

Environmental education has been around for a few decades, as part of a ‘back to nature’ movement. However, agriculture probably can teach ecology the best as it has a more applied side to it. So, I would opt for agro-ecology than normal agriculture. Of course, it depends on how you approach it. Working with natural materials has already been at the centre of alternative teaching methods such as Freinet or Steiner. It should no longer be confined to alternative practices. In Nepal, it's a bit more difficult as most people are engaged in agriculture and the mindset is still to get away from it. Nonetheless, many children also know how to grow crops. It’s a matter of reinforcing them, of appreciating what children already know by relating it to the curriculum. Teachers need to be convinced and they need to convince parents that knowledge does not only lie in books and that schooling is only for exams! Partly as a consequence of CEPP’s lobbying, the policy of having kitchen gardens in schools is already in place. The Ministry of Education has now issued directives for ‘Green Schools’. Not too far from Nepal, Bhutan has adopted Green Schools in a more comprehensive way. Even though we are still struggling with the availability of teachers and their basic training, implementing these learnings seems to be the way to go if we want to achieve a society where people live happily, in harmony with their surroundings. Teeka Bhattarai, Education Activist, Founder-Secretary of the Centre for Educational Policies and Practices, Nepal

Because we share Teeka’s / CEPP’s conviction that Nature should be protected and preserved, and that children growing up in the countryside should not be estranged from their natural environment, we designed a number of materials that are child-centred and that we hope will spark enthusiasm in both children and the grown-ups who educate them. We knitted a range of vegetables that are common to Nepal, as a friendly way of introducing the subject to young children. We made a fabric wall hanging about vegetables and fabric booklets about fruit. We made memory games about healthy eating habits and about the rural environment.

We laminated a number of pictures, that teachers and parents alike can use to discuss food and agriculture with the kids. We wanted the materials to be low-cost, handmade, beautiful, durable, simple and respectful of Nepalese cultures, things that can be replicated in Nepal itself too and that will help to create a happy atmosphere in the school environment. We made a set for the schools of Jutepani, Hakpara, Simras in Sindhuli District, Kalidevi (the location of the Post School in the village of Chapp, Makwanpur District), and one set for the CEPP office, to act as a source of inspiration for the team. We also provided one set for the Brick Children School.

It is our deep wish to introduce the toys and teaching materials in teacher training sessions in these villages, but because of Covid19, we will probably have to be very patient… In the meantime, we hope these educational materials can reach Nepal soon, so they can inspire CEPP staff and we can be inspired by their ideas and initiatives in return.

Paul Beké and Carine Verleye

If you wish to support CEPP’s efforts, your donation on the Bikas account BE 32 2200 7878 0002 will be very much appreciated. Please mention ‘From School to School’. Thank you for your interest and solidarity!